18' Great Northern Freighter Canoe

For those of you who have dropped by the shop, you know that you can always find at least a couple of boats being built. We very rarely however build boats for customers. Most of our builds are either for locals we know or more often than not are given to charities for auctions. This allows us to keep doing what we love to do (build boats), without having to purchase acres of land to store the boats we have built.

For those of you who have dropped by the shop, you know that you can always find at least a couple of boats being built. We very rarely however build boats for customers. Most of our builds are either for locals we know or more often than not are given to charities for auctions. This allows us to keep doing what we love to do (build boats), without having to purchase acres of land to store the boats we have built.

Over the last couple of years we have been asked a number of times to shrink our 20 foot Mi'kMaq freighter canoe to an 18 foot version. Well for those of you who have lofted boats, you know that there is more to it than to simply open a program, squeeze it down a couple of feet and hit the print button.

We received a call from a man in Texas a couple of months ago who not only wanted the 18 foot freighter canoe, but wanted us to build it for him as well. Now normally we would have said no but there were a few things which aligned to push us in the other direction. First, our friend in Texas has an issue which keeps him from building the boat himself, though he is certainly capable of using it. Second, we were just having meetings around here a few days earlier planning on our winter builds, so that shop would be available for the build. Lastly, we do send out a DVD with the Freighter which covers a good deal of the building project, however it isn't specifically for a freighter canoe and we have been looking for an opportunity to put together some more building instructions for that boat.

Long story short, we will be building an 18' Freighter canoe in the shop this winter set to launch in May of 2014 (or sooner). We debated filming the project, however we cannot pull together the resources under the time constraints we have to film for 200 hours between now and May. So what we will do is video segments to post here as well as a full building journal.

If you have questions or just want to chime in, you can ask them in the forum and we will be happy to answer. I hope you enjoy the journey.

Best Regards,

Jack Battersby

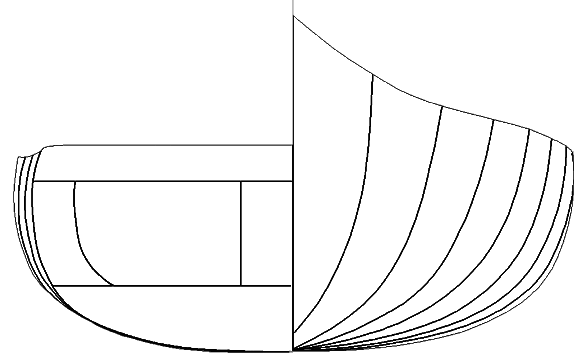

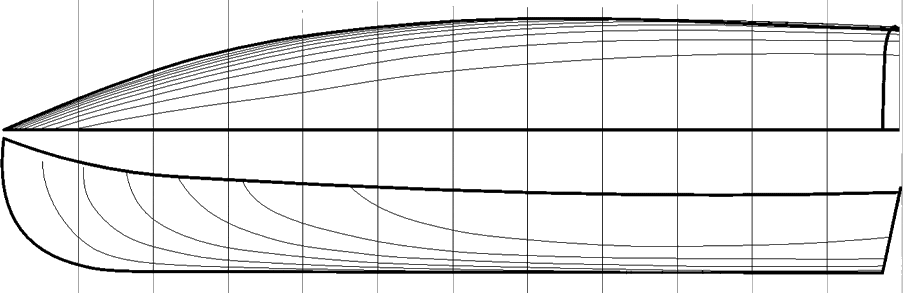

DETERMINING YOUR HULL MAKEUP

How to Determine my Hull Material for your Freighter Canoe

With most of our boats we simply give a list of suggested materials and people follow them. Materials for a boat like this are very dependent on the supporting components of the boat as well as the intended use of the boat. As originally designed, the 20 foot freighter canoe is to have a series of bulkheads; one at the termination of the deck, and one under each seat. This effectively breaks the hull up into 5 separate sections. With that small amount of exposure, a light weight hull could be achieved using ¼” X ¾” strips and 10 oz e-glass on the inside and outside of the hull with a double layer on the bottom inside and out.

The freighter canoe has proven to be a design that people want to fiddle with. That’s fine, wooden boats should be fiddled with to make them right for you. However, when you fiddle with things like bulkheads on a 20’ long freighter canoe you can get into trouble fast with hull flexing. So, in an effort to not pigeonhole builders into one method of building I am putting a few thoughts out there so that people can make some intelligent decisions and stay out of trouble.

Just like an aircraft wing, the outer shell is very dependent on the support structure holding it together. The shell combined with its supporting structure needs to be sufficient to counteract the forces being applied by waves pounding on the hull or the hull riding between waves.

Just like an aircraft wing, the outer shell is very dependent on the support structure holding it together. The shell combined with its supporting structure needs to be sufficient to counteract the forces being applied by waves pounding on the hull or the hull riding between waves.

The single most important thing to keep in mind is the bottom needs to be stabilized on a boat of this length and width. That can be done with bulkheads as suggested in the plans or floor supports and planking with the seats tied in with a post at each seat. The freighter canoe in this journal is being built with floor supports and planking. The floor supports support and stiffens the bottom from center up to the 3” waterline. These supports combined with the seat risers, seats and forward deck will stiffen the deck up nicely. It also allows for the free flow of water in the bilge with limber holes in each floor support. The patterns for the floor supports come with the 18’ version of the freighter canoe and the 20’ version will be revised to include these support patterns as well. If you have a previous version of the plans and wish to have these patterns, you can either make them by using the bottom 3” of each station mold starting from the first mold after the transom and stopping at the form just before the bulkhead location under the deck or you can write or call us and we will get them out to you.

While making your decision on whether to use floors or bulkheads consider the difference in height from the floor of the boat to the seat and decide if the reduction in space is acceptable to you.

TOUGHEN THE HULL UP

Before you determine how to skin your hull, you need to determine how you are going to use your boat. Builders tend to like the brightwork of the cedar hull showing through. As long as the internal structure is supported as discussed above, 10 oz e-glass used as outlined in the plans will suffice. 10 oz glass, particularly 2 layers of it will not be as clear as a single layer of 6 oz glass typically used on paddle canoes or kayaks. That said, it is not acceptable to use those lighter weight cloths on a boat of this shape or size. The single layer of 10 oz cloth on the sides of the hull will be clear enough for discriminating builders.

Here in the Cape Cod area of Massachusetts, our shores are sandy with very few rocks of any kind and sharp jagged rocks are near nonexistent. I do realize that not everyone lives here though, so here are my suggestions to combat the tougher shores of your area.

If you are looking to make your freighter canoe into a work horse to last a lifetime, then you will have to make a couple of accommodations for that. The first decision to make is if painting the hull is an option for you. The boat in this journal will be painted a deep green with trim of Ash and Sapele woods with a Sapele outer transom. The interior of the hull will be left brightwork and the wood will be on full display. Because of this decision, I now have the option to use some more exotic cloths. In this build I am using 10 oz e-glass as in the plans and that is then covered with a hybrid cloth of Kevlar and Carbon fiber. This cloth goes on just like e-glass however it is a very tight weave and the air bubbles need to worked out as you go. This is easily accomplished by using your gloved hand pushing the bubbles out and a fiberglass layup roller.

If you are looking to make your freighter canoe into a work horse to last a lifetime, then you will have to make a couple of accommodations for that. The first decision to make is if painting the hull is an option for you. The boat in this journal will be painted a deep green with trim of Ash and Sapele woods with a Sapele outer transom. The interior of the hull will be left brightwork and the wood will be on full display. Because of this decision, I now have the option to use some more exotic cloths. In this build I am using 10 oz e-glass as in the plans and that is then covered with a hybrid cloth of Kevlar and Carbon fiber. This cloth goes on just like e-glass however it is a very tight weave and the air bubbles need to worked out as you go. This is easily accomplished by using your gloved hand pushing the bubbles out and a fiberglass layup roller.

The upside of using this cloth is a very tough skin which will take the banging of the occasional rock or the beaching of the boat on a less than accommodating shoreline. The downside is it will add a few hundred dollars to the build and of course a little bit of time. However if you are combating the elements it is dollars and time well spent. This cloth Kevlar element is very abrasion resistant and the carbon further stiffens the hull for impacts.

The last suggestion for making your boat tank tough is the actual planking of the hull. If you are creating a real workhorse, and I mean a freighter canoe which will really be put through its paces, used constantly then you can take the above method of using e-glass combined with Kevlar/Carbon and put that over a hull which build from ½” thick planking instead of ¼” planking. I know that natural inclination of a builder is bigger is better, and in fact it is in this case, however consider if you really need this kind of toughness. It will undoubtedly yield a boat that with proper care will last a lifetime, but the boat will be heavier and the cost of the hull will literally double. You may want to consider this type of construction if you plan on using your freighter commercially for fishing excursions or you know you will be regularly be banging off of rocks or taking on high surf or swells. It is defiantly not needed for gentle rivers or flat lakes.

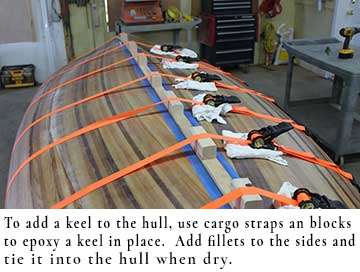

FINALLY, ABOUT A KEEL

My point in this history lesson and discussing the engine size is to get the point that the only real reason to have a keel on this boat would be a concern over sliding in the turns. For those of you who are inexperienced with this, it is when the bottom of the hull slides along the water in a turn. This is very common on skiffs, hydroplanes and other flat bottom boats. A freighter canoe is not a speed boat and shouldn't be treated like one. 10 to 15 knots should be the goal. You won’t be pulling water skiers, but you will get to where you are going a good clip. These freighter canoes can be used in a number of different ways. Historically their intended use was on wide easy flowing rivers for excursions or hauling materials up and down the river. As primarily a river boat, they tended to not have keels as that would only serve to make turning on the river more difficult. However I recognize that today’s boaters will likely be using them at least as much on the lake as they will on a river. Our freighter canoes are built to need only 10 to 15 hp engines for operation. We have a customer in Canada with a 20’ freighter and 10 hp ferrying 10 people up the Columbia River with satisfactory results. Older freighter canoes which were built with a completely different type of construction typically using frames, bulkheads, ribs and canvas were considerably heavier which is why you see people using 40 hp engines on them. These boats would tip the scale at over a thousand pounds.

These freighter canoes can be used in a number of different ways. Historically their intended use was on wide easy flowing rivers for excursions or hauling materials up and down the river. As primarily a river boat, they tended to not have keels as that would only serve to make turning on the river more difficult. However I recognize that today’s boaters will likely be using them at least as much on the lake as they will on a river. Our freighter canoes are built to need only 10 to 15 hp engines for operation. We have a customer in Canada with a 20’ freighter and 10 hp ferrying 10 people up the Columbia River with satisfactory results. Older freighter canoes which were built with a completely different type of construction typically using frames, bulkheads, ribs and canvas were considerably heavier which is why you see people using 40 hp engines on them. These boats would tip the scale at over a thousand pounds.

The benefit of not having a keel is greater maneuverability. As already pointed out, river turns will be much easier, and if you like fishing (and who doesn't), you will find getting into the perfect spot and swinging the freighter canoe about much simpler without a keel.

I hope this write up helps in your decisions, but if you still want to go over your options, feel free to contact us and we are happy to go through it with you.

PREPARING TO BUILD YOUR FREIGHTER CANOE

I have found over the years that making all the parts you need just when you need them is not necessarily the best way to work. So as boring as it may be, before we start putting anything together, we are going to cut and glue a few things first.

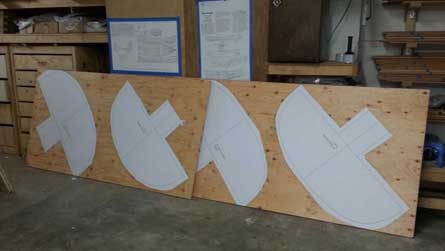

CUTTING THE CANOE FORMS FOR YOUR FREIGHTER CANOE

The forms for this canoe are no different from any other canoe with a couple of exceptions. They are about 20" wider than a typical canoe, and the transom is framed from hardwood and not a form at all.

The forms for this canoe are no different from any other canoe with a couple of exceptions. They are about 20" wider than a typical canoe, and the transom is framed from hardwood and not a form at all.

Because the body forms are so much larger, there are a couple of things you may want to consider. First, even if you have that big honking band saw, you may want to consider keeping it powered down for these guys. I have found it much simpler to use the Saber saw (otherwise known as a jig saw). There is a right way and a wrong way to do that. First off, all blades are not created equal. be sure and use a fine cut blade. It may go a bit slower, but it will be easier to control and will leave a smoother edge. Second and probably just as important, it is likely you have a switch on the side of your jig saw and if you play with that a bit, you will notice that it will push the blade forward and back at an angle to the cutting surface. There is a reason for that. If you flip it so that the blade bottom pushes forward you will find that you have a great deal of control and the cuts are very smooth. Most people never touch the switch, but give it a try it works well. You just need to remember to flip it back when you are making quick rough cuts.

All boat plans from us that say them come with patterns come with separate patterns for each station, cradle, floor supports and so forth. We do not stack patterns and make you trace them. There is too much room for error when you do that. That said, it is a simple matter of laying out the patterns on a piece of 1/2" plywood for the body forms use a little spray glue and gently and carefully roll them out. With patterns this size you may want to enlist the help of a willing soldier.

When cutting forms, I have always found that cutting just proud of and leaving the line is the way to go. By doing that you can take the cut form to a bench sander, oscillating sander or use a handheld sander to sand them right down to the line. That will give you a perfect form every time. If you have a bench sander it will take about 30 seconds per form to accomplish this.

One area to be particularly careful is the base of the form and the profile height. Take you time and get this right as it defines the entire profile of the boat. It isn't hard to get this right, just takes a bit of patience.

The stem form is different in that instead of using 1/2" plywood, you will be using 3/4" thick plywood. This is because your inner and outer stem will be 3/4" thick and it give a good landing surface to make sure you keep your stems straight. As you can see, we have out stem mounted in a bench vise with the holes cut into it for clamping the inner and outer stems as we glue them up.

The stem form is different in that instead of using 1/2" plywood, you will be using 3/4" thick plywood. This is because your inner and outer stem will be 3/4" thick and it give a good landing surface to make sure you keep your stems straight. As you can see, we have out stem mounted in a bench vise with the holes cut into it for clamping the inner and outer stems as we glue them up.

That is really all there is to cutting out forms from our patterns. Remember that we are not launching our boat to the moon. People get very nervous about it, but if you take your time and just keep it withing about 1/16th of an inch you shouldn't have any issues.

With the forms done, we can move onto our transom frame. Note the word "frame" and not "form". The transom frame will is a permanent part of the boat and as such care should be taken when choosing wood as you will be looking at it for some time to come. This boat will have an Ash frame and ultimately have 3/4" Sapele planks on the outside of the transom. Cutting out the pieces of the transom is virtually the same as the forms in that you use spray glue to glue the pieces down to the frame stock. I would suggest that where possible you start with a good clean flat side and match up what you can to save you a lot of cutting. You most definitely want to cut proud of the line and sand back in with these as well. When all the pieces are cut I use a dowel jig at each union. I don't do this so much for strength as I do to aligning pieces for glue up. The transom frame will be glued with thickened epoxy at all the mating surfaces and ultimately have planks on the outside so strength isn't an issue. Having a couple of dowels at each mating surface does however keep everything aligned nicely.

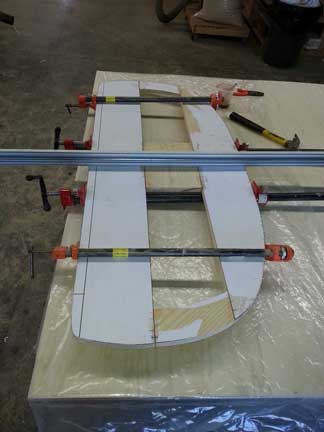

Once you have dry fit all of the pieces and you are happy with it, go ahead and mix some epoxy and wood flour together. Not too much wood flour, just enough to have a bonding agent but not enough to thicken the epoxy. The DVD details mixing epoxy for gluing. Also rememeber that clamping for an epoxy glue up is not the same as a yellow glue clamping. With yellow glue or carpenters glue you try to put a great deal of clamping pressure. With epoxy you try not to put too much pressure. Just enough to get everything held in place. If you clamp too tight it will squeeze out the epoxy and you will have a starved joint.

Once you have dry fit all of the pieces and you are happy with it, go ahead and mix some epoxy and wood flour together. Not too much wood flour, just enough to have a bonding agent but not enough to thicken the epoxy. The DVD details mixing epoxy for gluing. Also rememeber that clamping for an epoxy glue up is not the same as a yellow glue clamping. With yellow glue or carpenters glue you try to put a great deal of clamping pressure. With epoxy you try not to put too much pressure. Just enough to get everything held in place. If you clamp too tight it will squeeze out the epoxy and you will have a starved joint.

Before you walk away from your brand new freighter canoe transom frame, be sure and drop a straight edge across it to be sure that the clamps are not bowing the frame. It needs to be flat all the way across.

I like to try to do as much gluing with epoxy as I can as it is difficult to mix very small batches, so we went ahead and glued up the inner and outer stems at the same time as the transom frame so we wouldn't be throwing away to much of the stuff.

Next we will be going over the building of the strongback, but it is off to the shop right now. Can't build a boat from my desk chair.